PTSD & Trauma

NOTE: Brats Without Borders is currently producing Our Own Private Battlefield, a feature documentary about the inter-generational effects of combat PTSD on military children.

Click here to see a 7-minute clip of excerpts from the film.

Click here to donate and help pay for production costs.

Warning - Disclaimer!

The information below is intended to stimulate ideas, conversation and research. It is NOT intended as a substitute for consultation with a health care professional. Each individual’s health concerns should be evaluated by a qualified professional.

What Is PTSD?

PTSD stands for “Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.” It’s an anxiety disorder that some people get when they see or experience a dangerous or frightening event (like a war, or a car accident, or an earthquake) or series of events (like living with a traumatized, abusive, or alcoholic parent).

Some doctors just call it “PTS,” because they don’t consider it a disorder; just the normal way some human brains react when threatened. Whatever you prefer to call it, PTSD is real, and affects the lives of many military brats, young and old.

back to top

Who Gets PTSD?

Anyone can develop PTSD, at any age – even young children. It’s not just deployment-related and it doesn’t just affect soldiers.

You don’t have to be physically hurt to get PTSD, either. Military children and spouses can develop PTSD just from living with a traumatized service member (then carry it with them into adulthood). Some doctors call this Secondary PTSD; others just call it plain old “primary” PTSD. In essence, the service member’s reaction to the war (angry outbursts, anxiety attacks, excessive drinking) becomes the “dangerous or frightening event or series of events” for the child or spouse.

Not everyone who sees or experiences traumatic events develops PTSD, but it’s important to know the causes and symptoms, just in case.

How Does PTSD Work?

“PTSD is memory gone awry.””

In order to function, a person must be able to remember things. Obviously, we don’t remember everyone we meet or everything that happens to us, but we do usually remember things we need to survive, like how to chew and swallow.

We also tend to remember things that made us feel really good or really bad, like winning an award, saying goodbye to a deployed parent, or being abused. Those experiences get stored as memories.

There are two types of memories: explicit and implicit. Explicit memories are things like facts and ideas – things we remember when we hear particular words. Implicit memories are more subconscious, like how to ride a bike. We don’t usually think about how to ride a bike once we’ve learned. We just do it. Most of the time, traumatic memories are stored as implicit memories.

This is how PTSD works:

When a person experiences something traumatic (like war or child abuse), the brain releases hormones that help the person protect themselves in one of three ways, by: (1) fighting; (2) running away; or (3) freezing (if they can’t fight or run away). This is called the Fight or Flight Response. It’s important to remember that a person doesn’t choose whether they fight, run, or freeze. It’s an automatic reaction, depending on their experiences and genetic makeup. For example, many children freeze when they’re being abused, because they’re not big enough to fight back or run away. When they grow up, they tend to freeze in other traumatic situations, because they never learned how to protect themselves.

Once the trauma ends, the brain normally releases a hormone called cortisol that tells the person they’re safe and the threat is gone. The memory of the trauma is then stored in the survivor’s brain, and they can go on about their life, as usual.

Sometimes, however, the memory of the trauma doesn’t get stored correctly. It just keeps floating in the person’s brain, as if the trauma is still happening. They don’t think they’re safe, even when they are. Their brain keeps telling their body to prepare for attack. This is PTSD.

Imagine you’re in bed at night, alone in the house. Your roommate is at a movie. You hear a noise outside. You look around the room. The noise gets louder. You sit up in bed, scared. Your heart begins to pound faster and you’re barely breathing. You roll out of bed, quietly, and tiptoe down the stairs. Something crashes. You jump back. It’s quiet again. You peek out the window and see a neighbor’s dog digging through your trash.

At this point, if everything is working correctly, your brain releases the cortisol that tells you you’re safe and can go back to bed. Your brain stores the memory for you to laugh about with your roommate the next day.

But if you get PTSD from this experience (or already have it from other experiences), you can’t go back to sleep, because your brain is still telling you there’s an intruder outside. Your body is still tensed up to fight that intruder. Every little noise you hear, every little movement you sense, feels like a threat. This is what PTSD feels like. And it’s tough to deal with as a child or an adult.

back to top

What Causes PTSD?

trauma causes ptsd

In a nutshell, trauma causes PTSD. What kinds of trauma? Here are some examples:

Seeing or being a victim of violence, violent crimes, or terror

Seeing or being a victim of physical, mental, or sexual abuse

The death or serious illness of a loved one

War or combat

Accidents, like a car accident, plane crash, or drowning

Dangerous weather or fires

"Big T's Versus Little T's"

Some events, like a car accident or the death of a parent, are so awful that they only have to happen once to traumatize someone and potentially cause PTSD. We call these “Big T’s” or “Big Traumas.” Other experiences aren’t necessarily dangerous or frightening if they happen once – like being yelled at by your mother when you're young – but if you’re yelled at every day, no matter what you do, then it can rise to the level of emotional abuse and cause PTSD. Why? Because the moment you saw your mother, your body started preparing for attack. We call these “Little T’s” or “Little Traumas.”

Author and psychotherapist Stephanie Donaldson Pressman defines trauma as “anything that happens to you over which you have no control.” If that’s true, military children experience a lot of trauma in their lives – both “Big T’s” and “Little T’s.”

Here are some “Big T’s” military children can experience:

Constant exposure to weapons and other preparations for war.

Indirect exposure to the violence of war by witnessing its effect on a parent(s) or a friend’s parent (including anger, tension, depression, domestic violence, and/or self-medication with alcohol and drugs).

Direct exposure to war and violence during overseas assignments.

A parent’s death or (mental or physical) injury from war. If the family then leaves the military and moves to a new location, the teenager also loses his or her friends and community right when they need them the most.

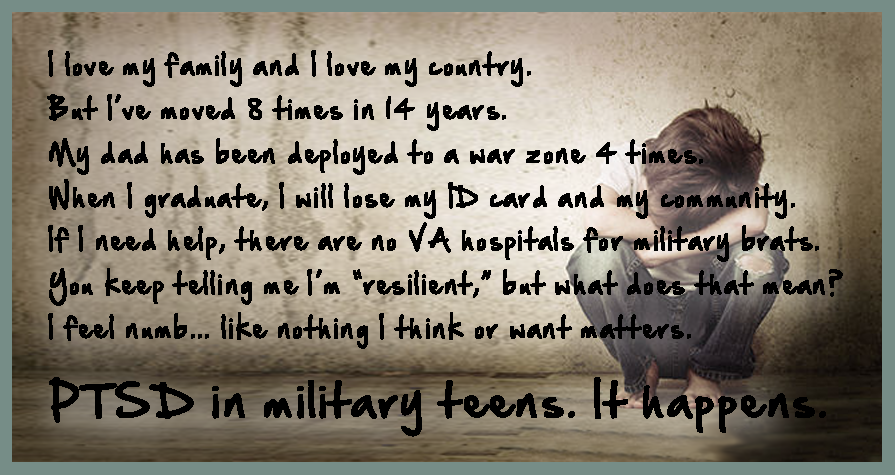

Here are some “Little T’s” military children can experience:

Multiple moves, in which a teen loses friends, teachers, coaches, team and club memberships, along with their reputation and educational status.

Parental absence due to training and/or deployment, so the parent is not available to help or guide the teen, if necessary.

Pressures to succeed, conform, and/or disregard a teen’s personal needs and desires because the teen wants to help (or not hurt) their parent’s career or the Military Mission in general.

it depends on the person

There is no “right” or “wrong” way to react to trauma. What is traumatic to one person may not be to another. And what’s traumatic to a child is not necessarily traumatic to an adult.

Let’s say, for example, Tricia’s mom is supposed to pick her up from school, but gets stuck in traffic and is an hour late. If Tricia is 16, she grumbles, calls her mom on her cell phone to complain, then sits down and reads a book until her mother finally arrives. If Tricia is six, the situation is not just inconvenient, it’s traumatic. Six-year-old Tricia is not just mad at her mom for being late; she’s scared her mother is never going to pick her up. How is Tricia going to feed herself? How is she going to survive? These are the things that run through Tricia’s six-year-old mind, even when she’s not really in danger.

back to top

How Do I Know If Someone Has PTSD - What Are the Symptoms?

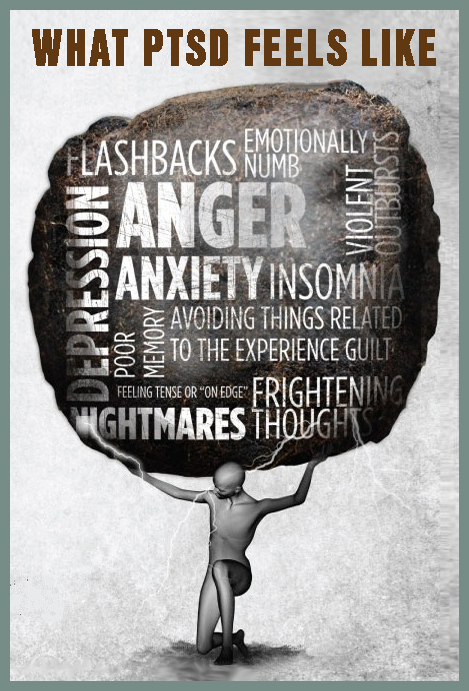

Only an experienced mental health doctor, like a psychiatrist or psychologist, can diagnose a person with PTSD. It’s natural, of course, to feel upset or scared when something bad happens to you or someone you know. But if the person is still upset or scared a month later, and exhibiting some of the following symptoms, it’s time to see a doctor – they may have PTSD.

categories of symptoms

PTSD symptoms can generally be grouped into the following symptoms: (1) re-experiencing; (2) avoidance; and (3) hyperarousal. Young children and teens also exhibit these and other symptoms.

When Chuck’s father returned from Afghanistan, he went to Chuck’s season opener baseball game, then never went back again. His father always had an excuse – he was tired, he had to work, he had a meeting. Chuck began to feel like his father didn’t care about him, anymore. In reality, Chuck’s father avoided the baseball games, because every time the bat hit the ball, his father flashed back to a day in Afghanistan when he heard a loud crack and his best friend’s truck blew up in front of him.

Mark’s mother was in a terrible car accident on a training mission in Okinawa. When she came home, she avoided driving as much as possible. She told Mark to ride his bike to soccer practice. Mark thought his mother was being lazy, when she was really just scared to drive.

Cara used to be a nice, easy-going, fun-loving girl before she moved to her third high school in three years. Now, she gets in fights over the tiniest disagreements. Cara thinks about cutting herself a lot and even tried it once. Cara may have PTSD from moving so much and losing so many friends.

| Re-Experiencing Symptoms | Avoidance Symptoms | Hyperarousal Symptoms |

|

|

|

military children and teens

Teenagers who experience trauma usually exhibit symptoms similar to adults. They can also act out, feel guilty, and have thoughts of revenge. Younger children often regress and act younger than they really are, and re-enact the trauma, instead of talking about it.

Other military-kid-centric events you should pay attention to are excessive moving and separation from a primary caregiver – both can cause PTSD in children and teens. Just because children can’t articulate their feelings doesn’t mean they’re not feeling them. Children under three can actually develop PTSD from being separated from a primary caregiver (due to deployment, training missions, etc.), exhibit symptoms as a teenager or young adult, and have no idea where it came from (because they can’t consciously remember the separation)!

Here is a list of common PTSD symptoms exhibited by children and teenagers:

| PTSD Symptoms in Children & Teens |

|

when do these symptoms start?

Again, it depends on the person. Some survivors exhibit symptoms soon after the trauma. Others appear perfectly fine, then months or even years later start exhibiting symptoms.

back to top

Why Do Some People Get PTSD and Others Don't?

Every winter, some people get the flu and some don’t. It’s the same with PTSD. People experience trauma every day. Some get PTSD and some don’t. They don’t choose to get the flu or PTSD. And they don’t usually “get over it” by just wishing it away.

Here are some things that make people more likely to develop PTSD after experiencing trauma:

If the survivor was close to or directly involved in the trauma.

If the survivor felt horror, helplessness, or extreme fear during the trauma.

If people or animals were hurt or killed during the trauma.

If the survivor lived through other traumas in the past.

If the survivor receives little or no support from their family, friends, or community during or after the trauma.

If the survivor experiences additional stress after the trauma, like a divorce or job loss, or if someone they care about dies or is injured.

If the survivor has a history of mental illness or anxiety.

Here are some things that make people less likely to develop PTSD after experiencing trauma:

If the survivor feels good about how they reacted during the trauma.

If the survivor was able to act/respond effectively during the trauma, despite their fear.

If the survivor asks for and receives support from their family, friends, and community after the trauma (including support groups).

If the survivor develops a coping strategy and learns something from the trauma.

The point is – try not to judge a person for getting (or not getting) PTSD. It depends on their genetic makeup, their life experiences, and a host of other things that are beyond their control.

back to top

How Is PTSD Treated?

The good news is – people can recover from trauma, both “Big T’s” and “Little T’s.” There’s no magic pill. It takes time and hard work, but it can be done.

First, find a doctor who is experienced with PTSD. The doctor will then help you find the treatment that works best for you. Treatment is usually psychotherapy (“talk” therapy), medications, or both. (You may need the medication to effectively participate in the talk therapy.) Remember, you are not “weak” if the doctor thinks you need the medication to get better. You wouldn’t tell a person with strep throat to “tough it out.” It’s the same with PTSD.

stages of recovery

“The core experiences of psychological trauma are disempowerment and disconnection from others... Recovery, therefore, is based upon the empowerment of the survivors and the creation of new connections... Recovery can take place only within the context of relationships, it cannot occur in isolation.””

In other words, you can’t recover from PTSD alone. Reaching out and connecting with others (family, friends, fellow survivors) is necessary to recover from PTSD.

According to Dr. Judith Herman, there are three basic stages of recovery from trauma:

- Safety. The survivor must feel safe.

- Remembering and Mourning. The survivor must tell their story and mourn what they've lost. (This must be done with a mental health professional, because talking about the trauma can re-traumatize a survivor.)

- Reconnecting. The survivor must reconnect with their ordinary life. As you know, this stage can be difficult for military families, because their “ordinary life” is constantly moving and changing. This is why it’s important for military brats, young and old, to stay connected with their “brat” friends, even if it’s just online.

Every survivor must go through these stages in their own way, at their own pace. The best gift anyone can give a person with PTSD is just to listen.

Psychotherapy or “Talk Therapy”

Psychotherapy or “talk therapy” is talking to a mental health professional alone or in a group. It usually takes 6-12 weeks, but can take longer, depending on the trauma, the survivor’s genetic makeup and experiences, and the support the survivor receives from their family, friends, and community.

During psychotherapy, the doctor may encourage the survivor to talk about a lot of things, including the trauma, their past experiences, and problems at home, school, and work. One of the most effective talk therapies is called Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. CBT includes the following types of therapies that work well with PTSD:

Remember Chuck’s father, who wouldn’t go to Chuck’s baseball games because the cracking bats triggered memories of the explosion in Afghanistan that killed his friend? Chuck’s father began going to a doctor who used exposure therapy. His father listened to cracking bats and other loud sounds in the safety of the doctor’s office, over and over again. Over time, his father’s brain grew used to the noises and didn’t automatically connect them to the explosion in Afghanistan. The doctor helped Chuck’s father retrain his brain. His father still jumps a little when he hears a loud noise, but he can go to Chuck’s baseball games again without reliving the trauma.

Cognitive restructuring. The doctor helps the survivor accurately remember the trauma. Sometimes survivors blame themselves for the trauma or feel guilty or ashamed of their own behavior before, during, or after the trauma. This happens a lot with children, who engage in such “magical thinking” as a way of controlling things over which they have no control. If they can control something, they can fix it, right? Wrong.

If the child is too young or traumatized to describe the trauma with words, the doctor can use games, drawings, or other “play therapy” to help the children process the trauma.

When Lindsey was 13, she was molested by a 25-year-old man at the base swimming pool. Lindsey became sexually promiscuous afterwards, equating sex with “love.” But then she felt dirty and depressed, and stopped dating altogether. When her mother discovered Lindsey cutting herself, she took her to a doctor. Lindsey told the doctor the molestation was her fault, because she flirted with the man at the pool. The doctor helped Lindsey understand that, even if she did flirt with the man, he was an adult who took advantage of Lindsey. The molestation was a crime, not a relationship between two consenting adults.

Stress inoculation training. The doctor teaches the survivor how to manage the symptoms of PTSD by reducing their anxiety and anger, through things like meditation.

Medications

The U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two medications for treating adults with PTSD: (1) Sertraline (Zoloft) and (2) Paroxetine (Paxil). Both are antidepressants. These medications can make it easier for the survivor to participate in talk therapy because they lower the survivor’s anxiety, sadness, anger, or numbness. The medications can have side effects, like headaches, nausea, and drowsiness, but they usually go away in time. Do not take without a doctor’s prescription and supervision!

Warning!

The FDA has found that some children, teens, and young adults can have serious side effects from taking these medications, including suicidal thoughts and actions.7 If you are 24 or under, do not take these medications without reading these warnings and consulting with a qualified doctor. The latest information from the FDA can be found on their website at www.fda.gov.

How Can I Help Someone With PTSD (Including Myself)?

There are many things you can do to help a person with PTSD, even if that person is yourself. Here are some suggestions from Dena Rosenbloom’s and Mary Beth Williams’s book Life After Trauma: A Workbook for Healing and other resources:

- You are not alone. Millions of people get PTSD every year because millions of people experience trauma. It can affect anyone at any age. Women and girls tend to get PTSD more often than men.

- Don’t despair. PTSD can be treated. You can feel better.

- Don’t hurt yourself (or anyone else). If you’re thinking about hurting yourself or anyone else, call 911 or a doctor right away. Do not isolate yourself or leave a PTSD survivor alone. There are trained counselors at the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

- Get professional diagnosis and treatment. Find a doctor who has experience working with PTSD and get help. If you’re helping someone with PTSD, encourage them to find a doctor, but don’t force the issue. Let them handle their recovery at their own pace. If you’re getting help and the symptoms don’t improve after 6-8 weeks, consider seeking different treatment.

- Treat the whole family, if they are willing. Trauma affects the survivor and everyone around them, so if possible, treatment should include the entire family. In a study of Croation war veterans, 39% of their spouses exhibited signs of secondary PTSD.

- Understand trauma and its impact. Knowing about trauma and PTSD before a traumatic event happens actually lowers a person’s risk of developing PTSD. For example, if a soldier is returning home with a physical (or mental) injury, prepare the children beforehand. That way, it’s not so frightening. If a parent pulls away, and you’ve never talked about PTSD, the children will just assume the parent doesn’t care about them.

Some parents are defensive about the very idea that their job or mental health could negatively affect their children. They insist children are “resilient” and moving is an “adventure.” While true, moving and deployment can also be sad, scary, and potentially traumatizing. If this is the case in your home, don’t give up. Find a more empathetic friend (or adult) and learn about PTSD on your own. - Find support systems. Support from others is critical when you’re healing from trauma – support from friends, family, teachers, and support groups. Sometimes the people you expect to help, don’t. (This can include your family and close friends.) Don’t get angry or upset; they’re doing the best they can. If that’s not good enough, find what you need from someone else.

- Communicate! Talk often with your family and friends, and be honest. If you’re feeling depressed, that’s okay. Try to think of positive things, too, and don’t give up hope. Learn about other individuals who have survived traumatic events and flourished, like Louis Zamperini in Laura Hillenbrand’s book, Unbroken, who survived a plane crash, being adrift in shark-infested waters for weeks, and a brutal Japanese POW camp.

- Help, but don’t try to “fix” someone with PTSD. Don’t try to make the feelings go away or assume you “know better.” If the survivor thinks you can’t handle their feelings, they may hide them, which will only make matters worse. Ask the survivor what you can do to help and really try to do it.

- Be patient. Healing from trauma takes time, support, and encouragement. Listen. Be understanding of the situations that trigger your PTSD symptoms (or someone else’s). PTSD survivors don’t react inappropriately on purpose or to be annoying. Keep reminding yourself – it will get better.

- Take care of yourself. Dealing with PTSD is hard enough. The more physically healthy you are, the better off you’ll be. Exercise, relax, meditate. Get your mind off of the trauma, if just for a little while.

- Maintain a safe and calm environment. Limit negative and/or violent news coverage, video games, and TV/movies.

- Be wary of predators. Bad people prey on the vulnerable, and PTSD survivors can be vulnerable, especially during recovery. This is also true for military children whose parents are deployed. If adults seem “too” nice or too willing to spend time with a child, be careful.

- Set small, realistic goals and stick to routines. As tennis champion Arthur Ashe once said, “Start where you are. Use what you have. Do what you can.” The same holds true for PTSD survivors.

- If helping someone with PTSD is taking its toll on you, don’t take it out on the survivor or expect them to take care of you. They simply cannot handle their problems and yours. Find whatever support or outlet you need elsewhere – from other friends and family.

- Get help sooner, rather than later. PTSD will not “go away” on its own.

Find Out More About PTSD

There’s a lot of information about PTSD on the internet, in libraries, and at your doctor’s office. If you or someone you know has experienced trauma, take the time to find out about PTSD. It can literally save a person’s life, including your own.

PTSD Resource Locations

The following locations usually have information about or provide assistance to PTSD survivors:

Mental health specialists – psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, mental health counselors

Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs)

Community mental health centers

Hospital psychiatry departments and outpatient clinics

Mental health programs at universities or medical schools

State hospital outpatient clinics

Family services, social agencies, or clergy

Peer support groups

Private clinics and facilities

Employee assistance programs

Local medical and/or psychiatric societies

The National Institute of Mental Health

The National Institute of Mental Health has many PTSD resources. You can find them online or write them directly at:

National Institute of Mental Health

Science Writing, Press & Dissemination Branch

6001 Executive Boulevard

Room 8184, MSC 9663

Bethesda, MD 20892-9663

Phone: 301.443.4513 or toll-free 1.866.615.NIMH (6464)

Email: nimhinfo@nih.gov

Website: www.nimh.nih.gov

Here are some NIMH fact sheets, if you want to find out more:

The National Institution of Mental Health's PTSD Research Fact Sheet

Antidepressant Medications for Children and Adolescents: Information for Parents and Caregivers

PTSD References

The above information was referenced in part from the following sources:

BRATS: Our Journey Home – a documentary film about growing up military and the profound effect it has on one’s adult life. Narrated by Kris Kristofferson. Features General H. Norman Schwarzkopf and author Mary Edwards Wertsch. Written and directed by Donna Musil. Brats Without Borders, 2006.

Brats Without Borders – the only 501(c)(3) nonprofit that serves both current and former military “brats” of all branches of service, founded by Donna Musil in 1998.

Free the Mind – a documentary film about using meditation to treat trauma, depression and anxiety, as well as build compassion and kindness. Features Professor Richard Davidson, one of the world’s leading neuroscientists. Directed by Phie Ambo. Kino Lorber Films, 2014.

Herman, Judith, MD. Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. Basic Books, 1997.

Moore, Bret A., Psy.D., ABPP, “Video Game or Treatment for PTSD?” Psychology Today, May 24, 2010.

Pedersen, Traci, “Military May be Turning to Meditation for PTSD” PsychCentral, March 2, 2013.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) booklet. National Institute of Mental Health, 2014.

Pressman, Stephanie Donaldson. BRATS: Our Journey Home (a documentary film written and directed by Donna Musil). Brats Without Borders, 2006.

Rosenbloom, Dena and Mary Beth Williams. Life After Trauma: A Workbook for Healing. The Guilford Press, 1999.

Rothschild, Babette. The Body Remembers: The Psychophysiology of Trauma and Trauma Treatment. W. W. Norton & Company, 2000.

Sidran Institute for Traumatic Stress Education & Advocacy

U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs. “PTSD in Children and Teens.”

U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs. “Very Young Trauma Survivors: The Role of Attachment.”

Wertsch, Mary Edwards. Military Brats: Legacies of Childhood Inside the Fortress. Brightwell Publishing, 2011 (2nd edition).

back to top

© 2014-15 Donna Musil. All Rights Reserved.